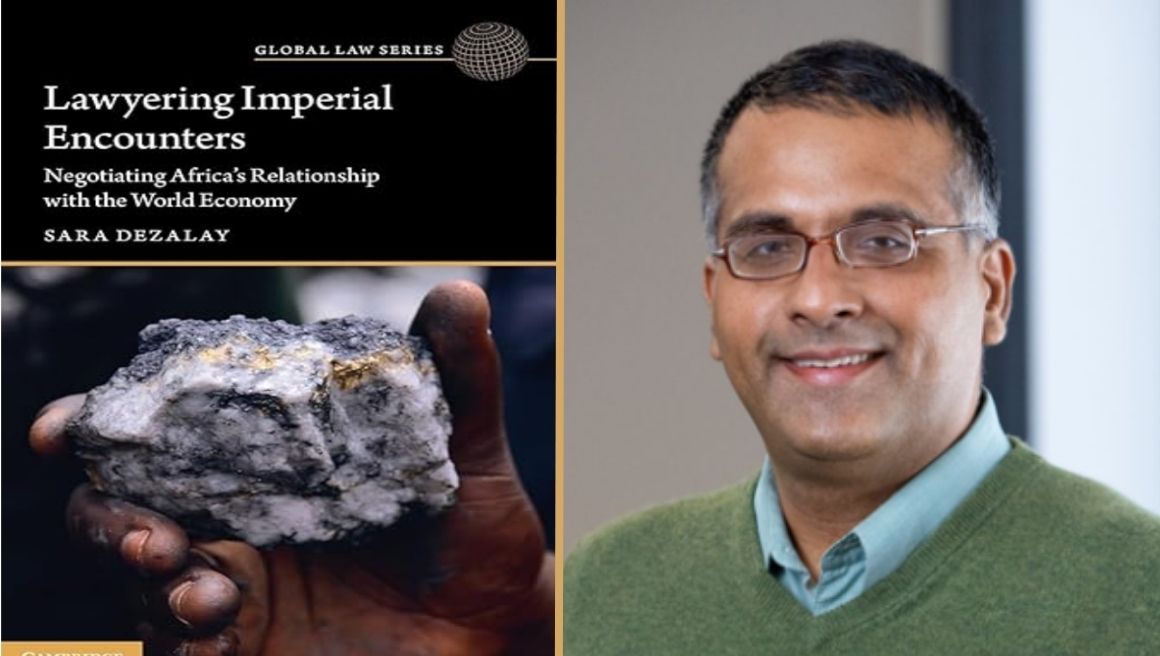

Through the Möbius Ribbon: Grappling with Dezalay’s Lawyering Imperial Encounters

Faisal Chaudhry

Among the more arresting features of Sara Dezalay’s timely and highly informative Lawyering Imperial Encounters: Negotiating Africa’s Relationship with the World Economy (Cambridge University Press 2024) is the full-throated commitment with which it opens to law as a two-sided coin. To borrow the book’s own preferred metaphor, law is repeatedly likened to “a Möbius ribbon,” as “both a fix and an enabler” to/of the colonial hangover characterising the titular relationship Dezalay’s purpose is to investigate. In this way, Lawyering Imperial Encounters sets its stage by setting aside what might be presumed an excessively “reductive” foil to the Möbius ribbon view—meaning, that which is cast, perhaps implicitly or just all too temptingly, in the garb of the proverbially doctrinaire Marxian who would otherwise have it that law is merely superstructural/epiphenomenal. In this manner, the Möbius ribbon image is evocative of how the ostensibly key intellectual challenge for the sophisticated surveyor is to be found in asking “where” we should “put the cursor of law’s empowering potential as opposed to its enabling role in maintaining the status quo”—for Dezalay, more specifically, the status quo “of the African South’s subsidiary position in the world economy” and presumably the status quo the juridical production of which is for the reductive observer all there is to chart about the law’s role in North-South economic relations.1

Lawyers as Empowering Resistance/Lawyers as Enablers of Extraction

Above, I say Dezalay’s book is “arresting” in part because her tour through the realities of the new-yet-old frontiers of extractive—and now in the 21st century, purportedly digital and green—capitalism is surely piercing. And to be sure, its redirecting scholarly interest in the offshore capitalism of tax havens, regulatory absence/repression, and generalised opacity onshore across various parts of Africa should be of relevance for observers far and wide across the global South. The resonance should go without saying for the countries of contemporary South Asia— where, headlines around growth rates and new eras notwithstanding, economies of resource extraction, special economic zones, and cheap labor remain alive and well. At the same time, “arresting” also proves suggestive with respect to how Lawyering Imperial Encounters’ master image of law as Möbius ribbon is referenced more than it is operationalised. That is, the monograph’s interrogation of the skewed relationship between the African places it alights upon and global capitalism in the aftermath of the 1884-85 Berlin Congress that kicked off high imperialism’s scramble for the continent leaves the reader tasting a seemingly quite different flavor than the introduction leads us to anticipate. This is because in chapter after chapter more than being served a course of lawyerly empowerment of countries in the African South against capital, the reader is left to imbibe much the same unpalatable vintage said to have left Marx’s lips through the idea apocryphally attributed to him of lawyers as capitalism’s clerks.

As we leave the book’s introduction and travel—from the post-scramble Gold Coast and Congo Free State in Chapter 2 to the early post-war British Copperbelt (today’s Zambia) and the former French colonies that have gone on to form the core of the CFA franc zone in Chapter 3 to today’s Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi, and Côte d’Ivoire, to say nothing of other parts far and wide like London, Paris, and Washington DC, in the remaining five chapters covering the period from 1980 to the present—it is not lawyers, and hence “the law,” as an empowering shield that Lawyering Imperial Encounters tends to bear witness to but the opposite.

Of course, here and there we do encounter instances in which long twentieth-century capitalism’s means of administratively extracting raw material commodities, from cocoa to cobalt, is said to involve more than just lawyers behaving badly/in service of profit and rapacious power. For example, reminding us that “empires are more than just giant states or the forerunners of modern states” and inveighing against “methodological nationalism,” while inserting the reader into the “cobalt pipeline” that terminates in the hand tools of some 100,000 artisanal miners in the DRC, Dezalay has us “zoom in onto the lawyer who coded” the “arrangement” of key nodes within the global value chain (GVC) that extends from those hands— via a path connecting the Congolese state’s Enterprise Générale du Cobalt, Transfigura, the world’s second largest metals and oil trader, China Molybdenum’s cobalt refining subsidiary Huayou Cobalt, and companies like Apple.2 So it is that we encounter Pascal Agboyibor, French-Tongolese son of Togo’s first corporate lawyer and human rights advocate, Yawovi Agboyibo. Casting his own intermediating role as following from his family’s origins in “elite groups of traditional West African warriors…dedicated to the defence of cities and states” in the region, the younger Agboyibor, Dezalay offers, carries a “profile” that “also symbolises a success story—that of a new generation of African business entrepreneurs and corporate lawyers intent on transforming the terms of the continent’s relationship with global markets.”3

Beyond Legal History/the Sociology of Legal Professionals: The Challenge of Critical Legal Economism

Yet where the line is more generally to be drawn between those wielding what Dezalay calls “middle power”— whether conceived as a kind of power particular to the intermediating role of lawyers, in specific, or just intermediaries, in general— and what others might once have called (or still call) a comprador element/ethic is hard to make clear. Indeed, it is not even clear that such a line must be drawn, including because whether it is worth drawing in the first place is a question that will be bound up with how any reader defines their own interests as between attending to the dynamics of the legal profession or those of global imperialism and historical capitalism.

As per its title, Lawyering Imperial Encounters is clearly a text the loyalties of which lie in the latter interest as much as the former. At the same time, Dezalay’s commitment to eschewing any implicit equation between the lawyer’s middle power and the comprador ethic imposes a certain challenge for its readers insofar as it is a matter of more than just style or, for that matter, a sense that academic styles have moved on from drawing such equivalences.4 Indeed, for those versed in law and development or critical approaches to private law as intellectual sub-disciplines, the principled basis for Dezalay’s theoretical construct of “middle power” will resonate and prove thought-provoking in potentially more than one direction. Captured in the book most frequently through reference to Katharina Pistor’s breakout 2019 work, The Code of Capital: How Law Creates Wealth and Inequality, the key analytical throughline of Lawyering Imperial Encounters can thus be traced through its emphasis on market dynamics being contingent on their underlying legal construction—viz. Pistor’s titular “coding”—together with related processes by which raw material commodities have been “financialised” amidst the rise of firms like Glencore and its bastard child Transfigura.

Of course, as celebrated as The Code of Capital has been, relative to the observations with which this contribution to the roundtable on Lawyering Imperial Encounters began, it may be worth considering—or at least, historicising—the possible limits of Pistor’s text as well. That is, underneath its idea of “coding” would seem to be a version of a staple insight that is now at least a century old within extra-Marxian heterodox legal-economic analysis of the kind pioneered by the first generation of legal/institutional economists in the United States: namely, that law (or, if one likes, “coded”/legal entitlements) determine the market. Yet focusing too intently on this staple insight can easily coincide with losing track of how already decades before the present, legal economism witnessed “conservative law and economics” itself, “accept[ing the insight] and parry[ing] by arguing that the market also determines the law.”5

To lose track of this history may thus threaten to obscure the analytical work that remains cut out for critical legal economism and that an ambivalent commitment to the Möbius ribbon image of law may inadvertently end up avoiding. Perhaps one way of measuring this threat would be to consider the possible advantages of going all-in on the ostensibly more reductive image of lawyers as capitalism’s clerks (or, perhaps just as well if not better, capitalism’s priests, as per the counterpart image apocryphally attributed to Thorstein Veblen).

This is because the other side of lawyers behaving badly/on behalf of rapacious profiteering need not simply be the notional idea of lawyers as “empowering” resistance to status quo colonial hangovers—even if this were among the real empirical concerns of Dezalay’s study, which, as noted above it tends not at any rate to be. Instead, “parrying” in the face of the idea of law determining/coding the market by emphasising how the market determines law can just as well serve to recast lawyering as a way of advancing the purported virtue of better price discovery (thus, re-enchanting rather than denaturalising market value). Accordingly, what to the critic can be made to appear darkly as speculation (say, in the face of Glencore’s “manipulating” the market through leveraging its contribution to transforming aluminum into a second-order financial asset as the same time as it was “hoarding” first-order supplies of the metal from 2010-13) may, after all, just as easily be made to appear by the booster as “efficiency-enhancing information aggregation” (say, in the face of Glencore’s baseline role in financially innovating; so as to precipitate market prices more reflective of supposed real world conditions).

To be sure, being left to turn back and forth around the axis of a generalised concept of financialisation is not only like but clearly related to being left to do the same around the axis of the law determining-the-market versus the market-determining-the law. Reading Lawyering Imperial Encounters through a fuller view of legal economism’s intellectual history is thus bound to enrich the text by rendering more apparent what analytical puzzles within the traditions of legal economism remain to be fully confronted.

Distributional Analysis, Capitalist Chains, and Value

One more specific line of pursuit consistent with an enriched reading of this kind is suggested from within the text itself through Dezalay’s passing reference to the enterprise of examining “the distributive effects of commodity chains” along the lines “set out by legal critical scholar David Kennedy of the Institute for Global Law and Policy (‘IGLP’) at Harvard Law School.”6 Yet it is not entirely clear if this constitutes a statement of purpose of Lawyering Imperial Encounters being an undertaking of the IGLP’s research manifesto or mainly just a nod of endorsement towards/sympathy with it.7 Of course, this may partly be a problem born from the IGLP Working Group’s blueprint, or lack thereof, for doing distributive analysis of GVCs rather than one to be attributed alone to a notional commitment to the Möbius ribbon view of law as carrying a “structurally dual role… as both an enabler for the expansion of power— through its symbolic function of codification— and as a check on petty arbitrariness.”8

Even so, it might still also then, in additional part, follow from the “embrace of chaos as a research agenda,” which Lawyering Imperial Encounters does in service of its further social scientific aim of advancing the sociology of the legal profession. Of necessity, this likely shifts Dezalay’s lens beyond any strict focus upon the analysis of value that GVCs beg. According to the IGLP working group, key to any such analysis is to gauge how law constructs and apportions/distributes the value that orthodox analysis would simply tally an “added” by each link on the way towards whatever ultimate end-user world of market prices. Yet as the working group itself acknowledges in calling for scholars to lean into this question, even in the best of circumstances there are “theoretical tensions” that arise “ineluctably at the interface between the Marxian theory of value, Schumpeterian conception of rents and Hale-ian analysis of coercion and bargaining power.”9 Accordingly, the illuminatingly “chaotic” journey through its African landscapes that Lawyering Imperial Encounters brings us upon might thus productively be complemented through more explicitly identifying— or grappling with— which of these competing paradigms for taking on the question of value best aligns with one’s own commitments. To be sure, if Dezalay’s way of proceeding in Lawyering Imperial Encounters is to be fashioned into a genuine research method by scholars of value chain capitalism as it pertains to other parts of the global South more explicitly clarifying where one sits at the interface between ideas like Marx’s, Schumpeter’s, and/or Hale’s could only be instructive.

For even in theory, there will likely not be the same demand for seeing lawyers as agents of enabling and checking rapacious power that emanates from the Marxian versus the Schumpeterian versus the Hale-ian perspective. For example, analysis in the Hale-ian tradition that starts from the neoclassical concept of value and surplus and then asks after how bargaining, including between labor and capital, occurs in the shadow of law will tend to offer a very different account of what is happening , across the production chain as compared to one that starts from Marx’s law of value and its own idea of surplus. Rather than intensifying the risk of an oversimplified view of lawyering, therefore, relative to the world at large there may be untold advantages in committing to a paradigm that would allow empirical realities to countenance a more rather than less “reductive” view of the lawyer’s role. After all, in a world beset by the law’s fetishisation, the reflex of seeing lawyers as wielding both swords on behalf of the powerful and shields against their power—even in the face of empirical facts in tow that seem to attest overwhelmingly more to the former than the latter—is bound to carry its own risks.

Law’s Rule, Law’s Ruins

Indeed, there has perhaps been no more apparent time in the post-war era when such risks should be regarded to have crystallised— at least for those seriously thinking about the world that empire and Western colonialism have left to the present. What, if not a tale of the impotence of law as a shield against rapacious power and its endless utility as a material and ideological sword, does “the world after Gaza”10 reveal? As if to put too fine a point on the matter, as the closing words of this contribution to this much-deserved roundtable on Lawyering Imperial Encounters are being drafted, news has broken of how United States-led sanctions on the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’)—as punishment for its daring to issue arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his former defense minister, Yoav Gallant in November 2024— have brought the Court’s work to a halt.11

The blowback for hazarding, for once, to check other than a proverbial “African/third world” leader has even tragicomically extended to American tech giant Microsoft revoking ICC Chief Prosecutor, Karim Khan’s access to his own email. And this all transpires against the backdrop of what the world over—except, by in large, within the halls of power within the West— has been understood to be a relentless now nearly two-year campaign of “live streamed genocide”12 against a largely defenceless Palestinian people whose place within the annals of colonial history, itself, has ever more vociferously been denied by the powerful.13 This, of course, has been even despite the shattering of the purported rules-based international order, which the apocalypse14 being forced on Gaza has so often been observed to portend over the last roughly two years. Yet notwithstanding the horror of people the world over who have been left to recoil at the relentlessness with which that apocalypse has been materially and ideologically advanced by “liberal” and “conservative” elements of the Western intellectual and political class alike, there tellingly has been no apparent cognitive dissonance within said class at continuing to make odes to the rule of law (of course, since the point is about odes to the rule of law, one is here leaving aside the role of various segments of the non-Western leadership in facilitating Gaza’s decimation— most obviously in the Middle East itself but also in other parts of the once proudly ‘third’ and non-aligned worlds, including South Asia).

To return full circle to the outset of this contribution, then, it must be up to scholars of good faith to remain open to the possibility that critical engagement with law and lawyering need not begin and end with an image of law as a Möbius ribbon of not only enabling rapacious power but also, reassuringly, empowering its contestation. As Lawyering Imperial Encounters’ empirical chapters themselves so well remind, in the reflection of the bruising reality of history and the present-day world, just as lawyers might more clearly be revealed to balance out as rapacious profiteering’s clerks so too might the law and its rule be revealed to balance out as the ultimate weapon against the weak. Surely, those artisanally wading through the wrong end of the cobalt pipeline in the DRC or, in the subcontinent, those in Odisha who only narrowly (for now?) escaped the use value of the Niyamgiri Hills being transformed into the Vedanta Group’s financialised bauxite value in exchange—to say nothing of those, most unfortunately of all, left to die in or be expelled from Gaza’s killing fields—might have a different tale, ultimately, to tell.

1 Sara Dezalay, Lawyering Imperial Encounters: Negotiating Africa’s Relationship with the World Economy (Cambridge University Press 2024) 11-12.

2 ibid 34. Here, Dezalay quotes George Steinmetz, ‘‘Focus on Pierre Bourdieu:’ Pierre Bourdieu, On the State: Lectures at the Collège de France 1989–1992, Cambridge Polity, 2014’ (2014) Sociologica 3, 9.

3 ibid 35.

4 ibid 28. As Dezalay pointedly asserts, for example, “[r]educing lawyers’ role to either collaborators or rebels obfuscates the structural function of law in shaping, justifying and transforming the relationship between these African sites and the global economy.”

5 Ramsi Woodcock, ‘A Progressive Critique of the Law and Political Economy Movement’ (Ideas,31 March 2023) <https://ideas.repec.org/p/osf/socarx/twbrk.html> accessed 20 June 2025.

6 Dezalay (n 1) 20.

7 The IGLP Law and Global Production Working Group, ‘The role of law in global value chains: a research manifesto’ (2016) 4(1) London Review of International Law 57–79.

8 Dezalay (n 1) 22-23.

9 IGLP Law and Global Production Working Group (n 7).

10 The turn of phrase is borrowed from Pankaj Mishra’s trenchantly titled The World After Gaza: A History (Penguin 2025), a work that that has, to some, failed meeting its titular aim. For a skeptical note see Sasha Frere-Jones, ‘Review: The World After Gaza– The Mistitling of Pankaj Mishra’s New Book’ (4Columns, 7 February 2025) <https://4columns.org/frere-jones-sasha/the-world-after-gaza> accessed 20 June 2025.

11 Molly Quell, ‘Trump’s sanctions on ICC’s chief prosecutor have halted tribunal’s work, officials and lawyers say’ (4Columns, 15 May 2024) <https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/trumps-sanctions-on-iccs-chief-prosecutor-have-halted-tribunals-work-officials-and-lawyers-say> accessed 20 June 2025.

12 See, for e.g., Amnesty International’s extensive reporting over the last two years in Amnesty International, ‘Amnesty International investigation concludes Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza’ (Amnesty International, 5 December 2024) https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/12/amnesty-international-concludes-israel-is-committing-genocide-against-palestinians-in-gaza/ accessed 19 June 2025; Amnesty International, ‘Israel/OPT: Two months of cruel and inhumane siege are further evidence of Israel’s genocidal intent in Gaza’ (Amnesty International, 2 May 2025) <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/05/israel-opt-two-months-of-cruel-and-inhumane-siege-are-further-evidence-of-israels-genocidal-intent-in-gaza/> accessed 19 June 2025; France 24, ‘Israel committing ‘live-streamed genocide’ in Gaza, says Amnesty International’ (France 24, 29 April 2025) <https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20250429-israel-perpetrating-live-streamed-genocide-against-palestinians-in-gaza> accessed 19 June 2025. See also the accelerating train of other authorities from international institutions like the ICC to scholars of mass violence. From two different ends of the chronological spectrum, see Raz Segal, ‘A Textbook Case of Genocide’ (Jewish Currents, 13 October 2023) <https://jewishcurrents.org/a-textbook-case-of-genocide> accessed 19 June 2025 and Omer Bartov, ‘Infinite License’ (New York Review of Books, 24 April 2025) <https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2025/04/24/infinite-license-the-world-after-gaza/> accessed 19 June 2025.

13 See, for e.g., Adam Kirsch, On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice (WW Norton 2024). For a review that is instructive in key ways, see Ran Greenstein, ‘Settler Colonialism Isn’t What You Think It Is’ (Foreign Policy, 15 November 2024) <https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/11/15/israel-palestine-settler-colonialism-south-africa-west-bank-gaza/> accessed 19 June 2025.

14 It is imperative to emphasise that while not a term of legal art like genocide, apocalypse is no simple rhetorical device. An essential labor of obfuscation that the western intellectual and political class has performed around what has been transpiring in Gaza has been to confound any serious discussion of death tolls. For the first year or more of the assault, as the official death toll ascended into the thousands and then past ten thousand, therefore, discussion within the Western press fixated on any such numbers being an overcount, typically claiming we must reflexively distrust Gaza’s health ministry (with esteemed journalists eventually thus opting to dub it the “Hamas-run” health ministry). Yet long after that health ministry, like all other governmental and civic infrastructure in Gaza, collapsed or was obliterated, this fixation was, in essence, dropped. Thus, with the clearly increasingly uncountable death count ascending and the only entity doing the counting unable any longer to do much of any kind of count at all, distrust of the official death count miraculously vanished. At the time of the writing of this piece, the official death count stands still only at around 57,000, a figure the increase of which has rapidly decelerated from the official count of 37,000 that was reached by 2024—sometime after the point when the Health Ministry’s ability to do any kind of count had likely fully collapsed and the Western press suddenly stopped fixing on doubting it. Of course, this all has been the case side by side with ongoing reason, not only form common sense but also ever reasoned efforts, to conclude that the official count was always a vast underestimate and an ever worse one at that as the Gaza Health Ministry’s ability to count has collapsed. Already by June 2025 the world’s leading medical journal, The Lancet, was calling the official figure a vast undercount (by at least 40%), given its correspondence only to deaths by traumatic injury rather what was already by then significant levels of starvation and disease. The necessarily conservative estimate of The Lancet, with the journal having been obviously unable to capture the unknowable numbers entombed under the rubble, has itself come to look ever more incomplete over time. For those willing to piece together the latest indicators, there is reason to surmise that a death toll in the hundreds of thousands is much more reasonable, which when added to mass displacement, traumatic injury, the decimation of whole family lineages, memories of what was readily counted as genocide in Rwanda, and so on tends to mark a convergence between the latter as a legal term of art and apocalypse as an apt term of ordinary language description. On The Lancet study, see Rasha Khatib, Martin McKee, and Salim Yusuf, ‘Counting the dead in Gaza: difficult but essential’ (2024) 404 (10449) The Lancet 237–238. On the present estimates putting the numbers plausibly in the hundreds of thousands, note that already by January 2025 some outlets were willing to report the figure of an over 150,000-person decline in Gaza’s pre-October 2023 population- see, e.g., Reuters, ‘Gaza population down by 6% since start of war – Palestinian statistics bureau’ (Reuters, 1 January 2025) <https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/gaza-population-down-by-6-since-start-war-palestinian-statistics-bureau-2025-01-01/> accessed 19 June 2025. More current efforts at reconstructing more plausible figures have drawn on statistics from the Harvard data-verse which are suggestive of a staggering 400,000 missing persons/population gap in Gaza— a figure which tends to track United States President Donald Trump’s references to some 1.8 million people now in Gaza (as compared to the 2.2-2.3 million before October 2023. For the Harvard data-verse dataset see, Yaakov Gar, ‘The Israeli/American/GHF “aid distribution” compounds in Gaza: Dataset and initial analysis of location, context, and internal structure’ (The Harvard Dataverse, 2025) <https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/QB75LB> accessed 18 Juen 2025. For an attempt to parse the data in terms of the consequences of the ongoing assault see Maximilian, ‘The grim arithmetic: IDF data reveals 377,000 Palestinians unaccounted for’ (Medium, 10 June 2025) <https://medium.com/@m4xim1l1an/the-grim-arithmetic-idf-data-reveals-377-000-palestinians-unaccounted-for-59f747490e61> accessed 18 June 2025.

Faisal Chaudhry

Faisal Chaudhry is an Assistant Professor in the School of Law at the University of Massachusetts and holds a concurrent appointment in the Department of History at UMass Dartmouth in 2022. Prior to his appointment, he was Assistant Professor of Law & History at the University of Dayton, where he taught courses on contracts, property, environmental law, and the history of capitalism. Previously Professor Chaudhry also has held positions as Visiting Professor of Law at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law and as a Post-Doctoral Fellow in the Departments of History and South Asia Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

As a legal historian, Professor Chaudhry’s research interests continue to focus on our understanding of the role of law and economy in the transition from the “early modern” to the “modern” ages (between the 18 and 20th centuries) in the Eastern Islamicate world. As a scholar of the contemporary world, Professor Chaudhry is generally interested in the legal-institutional underpinning of the market and the interaction between law, distributional justice, and sustainable economic development. More specifically, his research into present-day topics explore concepts of property rights and economic rent as they apply to land/natural resource use and the innovation system, both inside the United States and beyond its borders. His latest book, Towards a Historical Ontology of the Law (Oxford University Press 2024), considers the legal history of colonial rule in South Asia from 1757 to the early twentieth century. It charts a shift in the ontology by which notions and practices of sovereignty, land control, and adjudicatory rectification were aligned.