Micro-Dilutions and Administrative Resistance to RTI: An Analysis of Procedural Subversion

Far from being defined solely by its accomplishments, the 20th year of the RTI Act was dominated by a growing array of challenges. While the foundational threats driven by sweeping legislative changes are well-documented and widely articulated by civil society and experts, this article argues that the RTI’s utility is being subtly choked by the cumulative procedural subversions enacted by various public authorities, which I term ‘micro-dilutions’.

To understand the significance of micro-dilutions, we must first consider the foundational macro threats. So severe is the apprehension about the Act’s future that prominent activists who were once at the forefront of the movement are now forced to write of its decline, declaring that ‘The RTI is dead, long live the RTI’ and describe what was once called the ‘sunrise law’ as being in ‘sunset mode’. The systemic issues driving these threats include: the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act 2023, which statutorily restricts the disclosure of personal information, overriding the ‘larger public interest’ clause; the legislative curtailment of the Information Commissions’ statutory independence (2019 Amendments); and chronic executive neglect leading to defunct Information Commissions.

While reports, such as by the Satark Nagarik Sangathan (SNS) and the Commonwealth Human Rights Institute (CHRI), have consistently highlighted systemic, quantifiable issues—including numerous vacancies in Information Commissions, huge backlogs of appeals (exceeding 4 lakh in June 2025), and slow disposal rates—the crucial problem of micro-dilutions is less-discussed. Over the past two decades, many states have introduced administrative practices and sub-rules that create seemingly minor procedural hurdles. Individually, these might appear insignificant, but together, they coalesce into formidable barriers, making access to information increasingly difficult. Unlike the national-level amendments, which receive consistent scholarly, public, and activist attention, these micro-dilutions tend to fly under the radar.

The analytical foundation of this piece rests on primary procedural documentation from filing 50 RTIs across 26 states to collect data for a comparative study of state-level Grievance Redress Mechanisms (GRMs) as part of the Social Accountability Project at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru. The analysis is further informed by my experience of filing over 400 RTIs for research and advocacy in the last 4 years. This body of evidence demonstrates a distinct pattern of administrative resistance to RTIs.

The article details three representative examples of such procedural subversions: imposition of word limits; complicated payment methods and arbitrary charges; and the compulsory disclosure of identity and probing of applicant intent.

Unpacking the Micro-Dilutions

A. Arbitrary Application of Scope and Word Limit

Imposing restrictions on word count/the number of questions in an RTI application or arbitrarily deeming queries ‘voluminous’ has emerged as a common tactic to obstruct access to information. This intentional use of rigid application formats is a primary micro-dilution I encountered. Despite the RTI Act not restricting application length, several states and public authorities have introduced such limitations, directly violating its foundational principle and impeding access to information.

Take, for instance, my recent experience with a state department in Chhattisgarh.[1] I submitted an RTI seeking non-sensitive information, which should ideally be proactively disclosed, across 10 points regarding the state’s GRMs, encompassing the legal framework, budgetary allocations, and year-wise data on grievance volumes and disposal rates. The department refused the query, citing Section 7(9) of the RTI Act—a provision intended only to regulate the ‘disproportionate diversion of resources’—to summarily label the request ‘voluminous’ and deny it entirely. Recognising this common denial tactic, I refiled a simplified 2-point request. The application was rejected again, this time based on a 2006 state notification that limits the RTI provision to requests yielding fewer than 50 pages; anything more requires the applicant to visit the office to access the documents. This rule is a significant hurdle for applicants residing at a distance or with limited mobility and leads to requests being abandoned. Such mandates inflate the cost and effort for citizens and undermine the RTI Act’s core principle of accessible information.

Similarly, while seeking data on grievances received, resolved, pending, and their district- and department-wise distribution for Himachal Pradesh, I had to file multiple RTIs, whereas in other states—Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Punjab, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh—the information was provided in response to a single application. This was due to a rule introduced in Himachal Pradesh in 2006 mandating ‘a separate application shall be made in respect of each subject and in respect to each year to which information relates’. This unnecessarily cumbersome procedure deliberately multiplies the effort and cost in accessing systemic, multi-year data.

Bihar, too, has been enforcing a 150-word limit on RTI queries since 2009. My RTI application to a state department in Bihar was rejected on these grounds. On filing an appeal and securing a hearing, I received a partial response, stating that only 2 of the 10 questions could be answered as only they fell within the word limit. Such a word cap acts as a deliberate procedural barrier, compelling applicants to either truncate their original requests or entirely abandon comprehensive inquiries. This practice directly contradicts the 2012 Union guidelines, which stipulated that while RTI queries should ‘ordinarily’ be within 500 words, ‘no application shall be rejected on the ground that it contains more than five hundred words’. While states like Karnataka (which was the first state to set such a limit in 2008) and Maharashtra also previously imposed a 150-word cap, they appear to have since aligned with the Union guidelines. Bihar, however, persists in using this rule as a tool for rejection.

B. Payment Complications and Arbitrary Charges

Procedural obstructions also arise because state governments and their departments use sub-rules and interpretations to complicate the payment process, like the departments of Tamil Nadu and Kerala refusing to accept queries by Indian Postal Order (IPO). The Kerala RTI Rules stipulate that fees must be paid in cash or through demand drafts (DD). This ostensibly minor rule creates a significant financial and logistical barrier, especially for non-local applicants. To pay the basic application fee of Rs 10, a citizen must pay an extra Rs 25 as DD processing fee—tripling the cost and adding a needless, time-consuming step. Moreover, even with IPOs, their irregular availability in small, non-urban branches forces applicants to travel, imposing an additional financial burden. This was even acknowledged by the Central Information Commission (CIC), which once considered postal stamps as a more convenient alternative, though the idea did not materialise due to operational difficulties.

Furthermore, some Public Information Officers (PIOs) demand arbitrary postal charges, and a few states, including Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, and Haryana, explicitly mention these charges in their rules. This is despite Union rules declaring separate postal or courier fees to be unnecessary and a 2010 office memorandum from the Department of Personnel and Training explicitly stating that ‘PIOs should not ask the applicant to pay fees on such an account’. This additional fee makes seeking information more expensive and serves as a direct deterrent.

The Supreme Court of India (SCI) had to intervene in March 2018 to curtail the widespread practice of charging excessive fees. The court capped the application fee at Rs 50 and the per-page charge at Rs 5. While this ruling checked exorbitant fees, the use of other unjustified charges as a deterrent continues in new forms, including PIOs in Karnataka reportedly demanding an 18% GST on RTI and online RTI portals charging higher than prescribed fees or repeatedly failing to process payments.

This trend of micro-dilutions is also prevalent within the judiciary, as highlighted in the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy’s 2019 report, Sunshine in the Courts. The report revealed that many high courts charged exorbitant fees for RTI applications—the Allahabad High Court charged Rs 500 per application before the SCI’s intervention, while others, such as Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, only accepted court fee stamps. Similarly, the Bombay High Court mandates the inclusion of a self-addressed, stamped envelope with every application.

C. Demands for ID Proof and Intent

This category of obstacles directly contravenes Section 6(2) of the RTI Act, which states: ‘An applicant … shall not be required to give any reason for requesting the information or any other personal details except those that may be necessary for contacting him.’ Despite this clear mandate, several states and public authorities continue to circumvent this protection, shifting the administrative gaze from the information sought to the individual seeking it.

My RTI application to a state department in Haryana was rejected owing to a 2021 amendment that mandated identity proof. Despite initially ruling against it, the State Information Commission later upheld the amendment, citing Section 27 of the RTI Act and a 2012 Punjab and Haryana High Court judgment. This legalises a procedural barrier (until a higher court intervenes).

Even when an ID proof is not explicitly required, PIOs routinely initiate informal contact to ascertain an applicant’s identity and intent. For instance, PIOs often contacted me to clarify the purpose of my requests; upon learning they were for research, authorities typically felt satisfied and provided the information. PIOs also frequently use local addresses as a pretext to bypass formal RTIs, suggesting applicants ‘walk in’ and seek data informally instead, claiming their offices are ‘open to it’.

Though the RTI Act and subsequent rulings stipulate that seekers need not disclose intent, the informal probing reflects a deep-seated administrative bias. For instance, rejecting an RTI request, another state department in Haryana questioned how my RTI—seeking information about the functioning of the GRMs in the state—was in public interest.

The requirement of unwarranted identity disclosure is widespread. Even the CIC, which has at times fined PIOs for demanding ID proofs, once asked applicants to furnish photo IDs in 2015, only stopping after the practice drew negative attention in the Parliament.

Nonetheless, the practice persists, going beyond mere requests for identification—often escalating to demands for proof of citizenship or nationality—revealing a crucial pattern of subversion at the frontline. Such practices shift the burden of disclosure onto the citizen and serve as a pressure tactic to dissuade further inquiries. Crucially, they compromise the anonymity that provides a layer of safety to applicants, an essential protection given the documented deaths of over a hundred RTI activists in India.

Cumulative Deterrence

Despite numerous such micro-dilutions, citizens continue to navigate the labyrinth of RTI filing. In the recent acquittal of all 12 accused in the 2006 Mumbai serial blasts case (21 July 2025), the defence documents were derived from hundreds of RTI applications. This use of the Act to build a defence strategy in a terror trial mirrors other similar instances documented in Mayur Suresh’s book Terror Trials: Life and Law in Delhi’s Courts.

While such high-stakes cases highlight the Act’s power, it is more often a tool to solve everyday problems—from exposing irregularities in welfare programmes to securing delayed entitlements. The stories of its success are a testament to citizens’ constant pursuit of information, often out of sheer desperation. However, why should such relentless pursuit be required at all? A measure of healthy accountability and transparency mechanisms should be the ease of accessing information.

There may not be a single amendment that renders the Act toothless, but these micro-dilutions—arbitrary limits on the scope and word count, payment complications, and unwarranted attempts to ascertain intent—cumulatively create significant systemic barriers. In a graded society, they act as barricades that disproportionately push those with the least power and resources further into the information divide. A rigorous documentation and systemic assessment of these micro-dilutions become necessary to enforce the Act’s spirit of transparency and accountability.

As the RTI Act completes its 20th year and while we guard against major legislative changes, we must equally scrutinise these ‘paper cuts’—the micro-dilutions—to ensure the Act does not suffer death by a thousand cuts.

[1] Departmental names are omitted to foreground the systemic and recurring nature of these procedural hurdles, signalling that they represent a broader administrative culture rather than incidental departmental lapses.

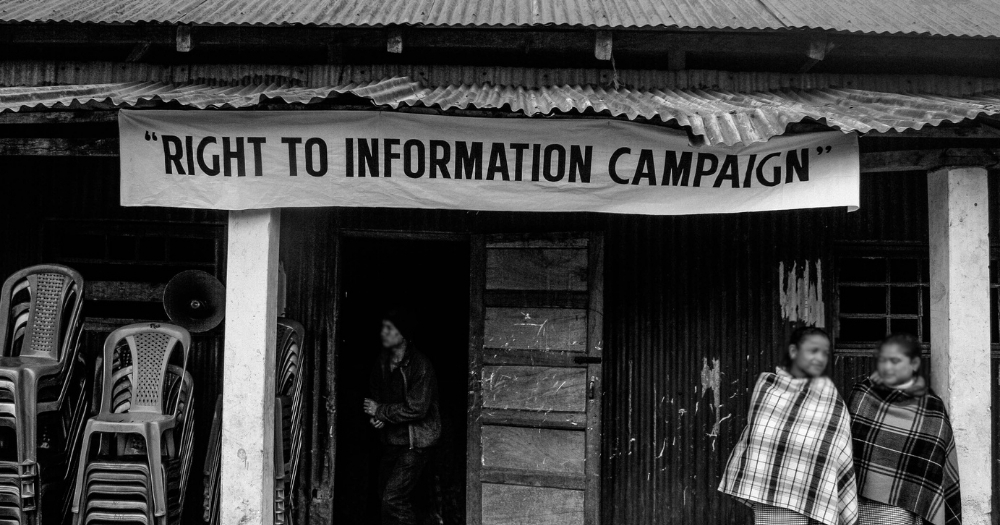

Photo from Mairang, Meghalaya during RTI Campaign, 2008.

Photo Credit: Tarun Bhartiya

Abhishek Punetha is Research Fellow, Theory and Practice of Social Accountability Project, NLSIU