Feminist Pedagogy as a Tool to Unsettle Expertise in Legal Academia

Rohini Sen

In this short analysis, I look to use two feminist pedagogical techniques – standpoint theory and relational analysis – to unpack the categories of ‘expert’ and ‘expertise’ in the domain of international legal knowledge-making through teaching. While the techniques are applicable to all forms of knowledge production, I specifically focus on a) teaching and b) international law to demonstrate the pre-coding of notions of experts and expertise into certain sites like gender, caste, class, classrooms, and certain disciplines like international law, in structurally Eurocentric, patriarchal and capitalist forms.

Before offering this analysis, it is important to talk about why I am working with these two analytical modes, and how they are different from other enquiries around ideas of expertise. Both standpoint theory and relational analysis look to contextualize the location and knowledge framework of the critical legal thinker (I use this term broadly to indicate critical thinking as a practice not limited to disciplinary ‘critique’) While the former unpacks the individual’s complex identitarian standing(s), the latter makes explicit the network of actors and processes that generate such standings(s). For instance, if standpoint theory makes apparent who we are (our gender, caste, class location and privileges) and how these identities give us structural power, relational analysis illuminates our relations not just with others but with these networks we inhabit and ideas we call value-neutral – such as law, knowledge and expertise.

These two analytical modes, among many others, collectively demystify the powers that shape ‘normative’ legal knowledge-making systems. They ask us to question our internalised impulses to assume, even in a somewhat caricaturist way, that a white European male scholar is an expert of international law by default, or that a positivist account of law is the only account of law, among other things.

Using these two techniques, and through the figure of the teacher-thinker, I hope to subvert two conceptual claims about intellection in international legal knowledge-making. The first is questioning the assumed role of teaching as secondary and at best adjacent to research in its capacity for knowledge-making. And the second, flowing naturally from the first, is questioning the dominant idea of ‘expertise’ in teaching as one that is rooted in hierarchical constructs (gendered, casteist, racist and classist) of conduct and training.

Teaching as knowledge-making

Let me begin with the processes that set teaching up for relative devaluation before I move on to the ways in which teaching of law produces knowledge. Teaching inhabits a complex position in neoliberal academia. While there are any facets of neoliberalism, I refer to two – a) employability matrix and b) quantitative metrics that measure and reward research and teaching. Higher education systems’ focus on employability has led to structural changes across the globe whereby subjects that are more likely to ‘generate employment’ are the ones likely to receive institutional funding and patronage. This is often at the expense of subjects that are perceived as more ‘theoretical’. The factors that determine whether a subject is viable for employability are often determined by the market forces. For instance, there is a growing proliferation of private law subjects in international law to cater to transnational global corporations, which seems to have deep epistemological impact on the education systems. If employability determines what subjects are to be taken ‘more seriously’, research metrics and quantification bears down on teaching in other ways. While most law degrees are teaching-centric, the association of publication indexing with institutional rankings (such as QS) places disproportionate focus on publishing, quantifying it in unhelpful ways. This can lead to a severing of the dialogical relationship between teaching and research as well as putting teaching in a position secondary to research given the relative difficulties in similarly quantifying it.

This is more challenging in certain geographies, where teaching carries with it the charge of being ‘more than a profession’, extending the task of teaching beyond the classroom to different forms of pastoral care. Thus, on one hand, teaching is not able to generate the same form of value and revenue through measurable impact as research is touted to do (referencing, citations, indexing etc). On the other hand, the social value assigned to teaching creates a complex hierarchical system of porous, unpaid labour, without addressing any of the structural constraints around institutional academia. While there is value in calling it a vocation, it also opens up the space for romanticising more unpaid work in existing inequalities. In all of this, there is also often the underlying the perception that teaching is transmission of existing knowledge whereby research is the production of something ‘original’.

I offer this framework to understand the structures within which teaching works and the ones that shape it as a social process. I arrive at this framework using standpoint theory to understand the shifting paradigm of teaching – as a teacher of international law, as a researcher who studies international law teachers, and other intersectional identities I inhabit. Relational analysis serves the function of recognising the relationship between teaching and research, between different forms of law teaching, between the public and private and between various forms of labour that are foregrounded and hidden. I look to analyse the teaching of law within this complex network of actors and processes where it is done. The teaching of law is typically done as a professional degree whereby most of the curricula tends to the fact that one is training a legal professional. This often leads to a disproportionate emphasis on questions of ‘practice’ and ‘interpretation’ outside of their embedded contexts. For instance, teachers of procedural law, and sometimes even substantive ones, assume that ‘theoretical engagement’ is not relevant to what they are doing – positioning theory as extrinsic to law rather than something that undergirds all of it, including its teaching and especially its doing.

Relational analysis allows us to rehabilitate theory-praxis-practice for what they are – dialogical interactions rather than as two separate areas of operation. Importantly, international law has a particular dimension to this practice oriented teaching as well. Practice is seen as something that is done ‘elsewhere’, in the Global North approximately, which leaves Global South international law teaching to be more theory-oriented and/or disconnected.

Using the two analytical tools from before, I argue that the teaching of international law, especially when done in critical ways, produces knowledge about the discipline, absence of institutional practice notwithstanding. The aim of critical teaching is to produce the legal professional while balancing other critical, ethical considerations. In teaching critique and critically, other subversive aims come to the fore from such teaching – acting as the counterpoint to knowledge-making in the way teaching does to research. When critical teaching of international law is done, there are two ways in which teachers make knowledge. The first is by bringing in their own social, political and intellectual biographies and experiences into the classroom in the form of contextual and interpretative knowledge. The second is through actively teaching structural critique and alternate narratives. Through these embodied knowledges, and through the teaching of critique – teachers augment one’s understanding of law, thereby generating knowledge about the discipline. This is done in tandem with research as well as solely in the classroom as an arena of exchange. This is not limited to critique but any kind of teaching of international law that looks to augment the meaning of law and put it in multiple histories and contexts. Elsewhere I have spoken of why this is peculiar to international law in more ways.

Expertise

It is within this framework that I locate my analysis of expertise in international legal academia. While there are indeed overarching patterns traceable to all academic disciplines, legal academia comes with its own set of disciplinary practices that inform both this teaching paradigm and the notion of expertise in it. I use the same analytical tools to now turn to the idea of expertise. Expertise, suggests Alexandra Horowitz in her treatise on mindful walking, is ‘the power of individual bias in perception — or what we call “expertise,” acquired by passion or training or both — in bringing attention to elements that elude the rest of us.’ It is this definition of expertise that I work with to bring to attention what we generally miss about it in academic institutions and teaching practices. Legal academia, and particularly international legal academia, understands the notion of ‘expertise’ as a definitive, deterministic account of disciplinary positions and givens. For instance, it examines who may define law, which is followed by and determines how law may be defined, what are its sources and where such sources may find themselves hierarchically in practice. Those who take upon the task of definition based on historical hegemony and power simultaneously set the terms of such definitions and their remits as well. Inadvertently, the international legal expert is one who defines the law, knowledge about the law and what needs to be done to attain expertise in such knowledge in a self-serving process.

This traditional construct of legal expertise is deeply intertwined with systemic hierarchies and defined by criteria that privilege certain hegemonic identities (Eurocentric patriarchal, illustratively) while marginalizing others. For instance, gatekeeping practices in academia, such as the misplaced conflation of elite credentials with knowledge and rigour (a presumption that degrees from Oxbridge are automatically equal to knowledge); gender-class-race-caste informed practices of rigid scholarly conduct (an insistence on “objective research” which has been critiqued by feminists and multiple other critical traditions); disproportionate emphasis on mainstream legal languages (most international law documents are in English and/or French) and textual, ‘technical’ knowledge (the positivist method) exclude other cosmologies of knowledge and possibilities of expertise (indigenous legal systems, scholars who do not study in elite universities or, come from contexts that are not American-European). In international law, such expertise is often associated with particular figures such as Grotius, Vittoria and other figures closely associated with colonial expansion, who are often hagiographed as “fathers” of international law,. In modern day international law, this extends to other Euro-American forefathers, including those from critical traditions as well, though of much less relative valence. Such “fathers” and experts are seen as sacrosanct, representing authority, credibility, and mastery of law, where what they say about the law is an unquestioning paradigm, demonstrative of their rigour and not speculative theorising based on perspectives and constructs. In other words, such notions of expertise reveal to us no more and no less than the socio-political context of where such experts come from and what kind of disciplinary trainings shape their perspective. This means that, rather than expertise, these ought to be treated as one kind of contextual and informed perspective on/of international law in relation to many others (TWAIL, Feminist Marxist, Latin American, Indigenous, among others). To be clear, I am not suggesting that one cannot attempt to make bigger, generalised theoretical formulations from specific locations and trainings. That should be the task of all rigorous scholarship. My argument here is different. I am suggesting that expertise of different kinds be put in context rather than be taken as an universalising impulse especially when it runs the risk of being associated with certain marks of privilege. All knowledge is partial knowledge and all forms of knowledge come with their associated politics.

The other kind of expertise one has to be mindful of in such teaching is the kind of expertise that classrooms generate. While all those who enter a classroom with the presumption of disciplinary knowledge, not everyone who enters is touted to be an expert. There are certain things that are pre-coded into the idea of such expertise such as one’s gender, caste, class, race which one often has to work against. For example, an expert of international law in a classroom is more likely to be a visually professorial figure – an old male professor or even a senior female professor, although the latter is more likely to be slotted as a gender expert than a general expert. Thus, while knowledge is indeed disrupted when we say teaching produces knowledge, it still comes coded in other forms of inequality, through the idea of an expert teacher and how we assign expertise to professorial figures. What is interesting is that even as expertise in teaching is pre-coded as gender-caste-class-race, the unique position of the classroom as a place of orthodoxy, authority and designated site of knowledge exchange somewhat complicates this precoding. Students come to classrooms to learn and “receive” knowledge; teachers come to disseminate them as relative figures of expertise and authority. No matter how diffused and non-hierarchical a classroom is, especially in the case of postgraduate courses, this underlying configuration remains. Even as teachers may try to displace some of this authority through pedagogical reflections, students turn to classrooms as a place of characteristic authority of the teacher where canons come to life and knowledge is imparted, notes Sharmila Rege. The teacher may be accessible, their authority may be diffused, but they always remain figures of authoritative expertise, even as they are challenged by structural precoding. The two analytical frameworks help us understand the complex interplay of factors that make up the notion of expertise in the teaching of international law rather than ascribing simplistic values such as expertise is equal to unquestioned knowledge on the discipline.

The feminist critique I make of such a form of expertise is that such ascriptions are rooted in hierarchical structures of gender, race, caste, and class. Feminist pedagogy, with its transformative methodologies, offers a powerful lens to challenge these constructs and reimagine the figure of the expert who creates knowledge in a given discipline. By employing feminist techniques such as standpoint theory and relational analysis, we can question and subvert as well as transform traditional notions of expertise meaningfully, shifting the focus toward inclusivity and democratisation of legal knowledge-making and academic practices. Standpoint theory emphasizes that knowledge is situated and shaped by the social positions and lived experiences of the knower. For international legal academia, this means that the identities of legal scholars are profoundly shaped by gender, race, caste, class, and lived experiences and consequently, inform their perspectives. Standpoint theory disrupts the notion of an objective, universal “expert” in international law by both challenging Eurocentric universalism and highlighting the relevance and presence of diverse, contemporaneous perspectives such as CAIL, TWAIL, and feminist approaches to international law, among others. As a feminist heuristic, it allows us to see every position as a vantage of partial knowledge, especially the ones that present themselves as universal. To that end, the universal posited by the ‘expert’ is really just one form of the provincial, while many other parallel ‘universals’ can be culled out from many such equally relevant vantages.

Similarly, relational analysis allows us to understand the many relationships between ideas, concepts and institutions. Examples of some of these relations are – who forms the basis of current ideas of expertise, how do they stand in relation to others and what kind of power and hierarchies operate between each of them. It focuses on the networks, systems, institutions and practices that create and sustain constructs like ‘expertise’ where knowledge, authority and objectivity are vested by default in the white male scholar and his racialised proxies elsewhere. Consequently, it examines the interplay between individuals, institutions, and processes that define and determine what it means to be(come) an ‘expert’ in legal academia. Relational analysis is able to make these complex networks visible, thereby demystifying the power structures that uphold and sustain traditional hierarchies of knowledge-makers and their knowledge. In revealing them as socially constructed and inherently limiting, relational analysis allows for newer, inclusive and collaborative forms of expertise to emerge. Together, these techniques and frameworks provide a critical lens to deconstruct expertise and reimagine the role of teaching and knowledge production in international legal academia.

I refer to these two techniques to demonstrate how feminist pedagogy allows us to reimagine the role of the teacher, the expert and the teacher as a knowledge-creating expert. In traditional and neoliberal academia, the teacher is often seen as a transmitter but not a creator of knowledge. The authority of such teacher figures is derived from hierarchical notions of who can rightfully be knowledgeable and what forms such knowledge can take. In other words, there is default ascription of prefigured expertise as well as prefigured practices of knowledge-making. Feminist pedagogy disrupts this social prefiguration by first positioning the teacher as a co-creator of knowledge. I begin by recentring teaching through such techniques because there inheres a degree of gendering in the value assigned to teaching itself in relation to legal research and other forms of practice even as the idea of an international legal expert in the domain of teaching remains intact. Following this, feminist heuristics and pedagogy unpack and challenge such entanglements towards deconstructing the very notion of expertise. In integrating the complex terrain of insight from lived experiences into theoretical rigour, feminist pedagogy is able to imagine some conditions for democratising legal knowledge-making. Through standpoint theory and relational analysis, among other techniques, it is possible to unmask, unpack and challenge the hierarchical constructs that have long-defined international legal knowledge-making and expertise. The task of such feminist approaches and critiques is to disrupt traditional notions of expertise, and also to reposition law teaching as a central site of intellectual creation, instead of disproportionate emphasis on research and institutionalised forms of practice and dated notions of who is an expert and where such expertise comes from.

Paper presented at the ‘Teaching International Law’ Panel, sponsored by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Chair of NLSIU, at the 10th International Conference on International Law: Issues & Challenges, organized by the Indian Society of International Law on 25-27 October, 2024 in New Delhi.

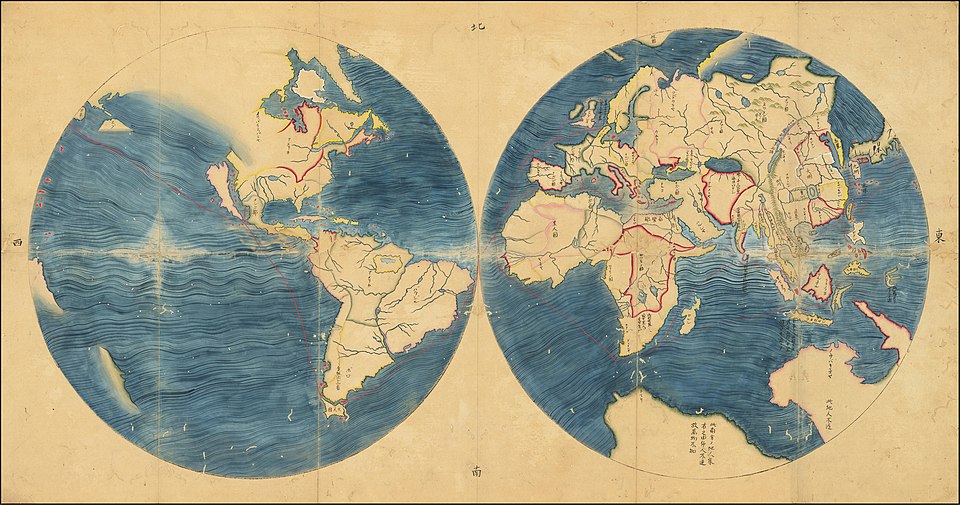

Image credits: Willem Janszoon Blaeu / Anonymous.

Rohini Sen

Rohini Sen is an Associate Professor at the Jindal Global Law School and teaches as a Visiting Faculty in different institutions across India and abroad. Rohini thinks about, reads and writes on the various engagements between Law, Sciences (Social and Natural) and Humanities through ideas of - critical thinking, critical pedagogies, queer and feminist approaches and, different cosmologies of knowledge-making. Alongside her institutional academic work, Rohini is also one of the co-founders of the Feminist TWAIL Collective (a network of feminist scholars working on critical feminist engagements with TWAIL specifically and international law broadly) and the THRIvE (Transformative Holistic Research for Integral and Inclusive Education) Research Centre which reimagines education systems for holistic and integral education of learners at all levels.