Growing Integration and Inward-looking Normativity of International Law: Do We Need a New Pedagogy?

Akhila Gangadhar Basalalli

This paper stems from two key sources: my research interest in the interaction between international law and municipal law, and a few years of teaching international law. From a combination of these experiences, I have come to realise that there is little attention given to the impact international law has on a domestic legal system. It is intriguing to consider the development of sectoral regimes and the influence of international norms on municipal laws governing these regimes. The sectoral regimes are various areas of international law that are regulated by multilateral instruments rather than bilateralist structures. Many areas that were traditionally and predominantly state-centric now feature multiple and co-substantive norms (where identical norms are present in both international and domestic legal systems). Examples of sectoral regimes include human rights, environmental law, refugee law, labour law, law of the sea, and commercial arbitration, to name a few, all of which demonstrate the growing integration between the legal systems.[1] The norms of such sectoral regimes have been judicially incorporated into the Indian domestic legal system, where they continue to play a regulatory role.

Pedagogical Isolation

The paper attempts to discuss a few pedagogical limitations on teaching and understanding the interactions between the legal systems. Firstly, the subject of international law remains pedagogically isolated, and suffers as a result of being taught under one head or domain, rather than as a recurring theme across specialised areas of international law and other disciplines. Secondly, the Indian courts have demonstrated great eagerness in implementing international legal principles into their domestic legal system without critically interrogating their formative process. This enthusiasm to align with international expectations has been marked by the courts overlooking the critical and/or intersectional lens, resulting in significant social fallout.

Teaching and learning international law in the Global South has mostly been marked by the entrenched and polarised rhetoric of mainstream understanding,[2] while remaining oblivious to the effects of growing integration between domestic law (of any Global South state) and international legal systems. Since international law does not determine the methods or patterns of its domestic implementation, there is no definitive explanation of how domestic courts engage with international law or how they interpret and apply it. A study of decisions of the Indian courts (with a few exceptions) demonstrates a growing enthusiasm for devising techniques and tools to integrate the legal systems, such as by reading international law into their decisions, co-citing international and domestic laws, and interpreting domestic law in light of international law, to name a few. This pattern of systematic and normative convergence is blurring the distinction between the two legal systems, and merits further analysis.

It is interesting how the normativity of international law has changed from being outward-looking and governing international disputes, to an inward-looking system for states’ own regulation, a phenomenon best described in the ‘ILA Study Group on Principle on Domestic Courts Engagement with International Law Report 2012 and 2016’. This idea of ‘inward-looking normativity’ requires states to undertake certain conduct within their own domestic order: to adopt a specific legal framework, to accord individual rights, to abstain from taking action. For instance, international human rights law may accord protection of specific rights, or international environmental law norms may set curbs on emissions, or create obligations to grant access to information, justice, or to allow participation in decision-making. The emergence of sectoral regimes propelled by international conventional laws and international organisations have facilitated the development of international laws from a traditional model based on states’ consent at every step, into one grounded in a consensual ethos. The domestic state organs (mostly the judiciary) have resonated with this shift, which has intensified the need for a nuanced and critical understanding of the legal consequences of this increased interface between domestic and international legal systems, especially given its hegemonic character.

Limitations of the Pedagogical Engagement

The paper presents a set of limitations on the pedagogy of the subject, transforming it into another sociologically neutral investigation.[3] Firstly, there exists a pedagogical and analytical limitation of isolating the subject of the interface between the two legal systems into one theme: this is often seen in Indian judgements as a discussion of traditional theories, a few state practices as sample studies, and an account of India’s increased enthusiasm for engaging with international law. This is often followed by a recital of constitutional provisions without really evaluating the trend of the engagement and its repercussions. Furthermore, the engagement is also not offered as a recurring theme across the subjects of international law and sectoral regimes such as human rights, environment, gender studies, and refugee studies, to name a few.

Secondly, the approach adopted in teaching and learning the relationship between the legal systems demonstrates extensive engagement with judicial decisions, emphasising the methods and techniques used in implementing international law into municipal law. Such a neutral pedagogy demonstrates minimal attention paid to the formative processes of international law. In the decisions where the courts have read customary international law into Indian decisions, treating them as equivalent to the law of the land, there has been insufficient examination of the nature of these norms and whether they truly qualify as customary international law. For instance, the Supreme Court accorded the polluter pays principle the status of municipal law in the Vellore Citizen Forum judgement. It drew the concept of sustainable development from the Stockholm Declaration 1972, the Brundtland Report 1987 and the Rio Declaration 1992, and cited these sources by stating that “we have no hesitation in holding that ‘sustainable development as a balancing concept between ecology and development has been accepted as a part of the customary international law though its salient features have yet to be finalised by the International law”. This uncertainty aside, it also identified and applied as given principles such as the precautionary principle, the polluter pays principle, intergenerational equity, and environmental protection, despite the actual uncertainty surrounding their status as customary international law.

Finally, when Indian courts read international human rights instruments into domestic laws to fill gaps, they often ignore critical and intersectional perspectives. For instance, Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan is celebrated as a decision which has expanded the ambit of Articles 14, 15, 19(1)(g) and 21 of the Indian Constitution by reading into them the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (‘CEDAW’), 1979. While this decision emphasises gender, it fails to consider the implications of caste, thereby missing an intersectional perspective. Similarly, in the NALSA judgement, the Supreme Court referred to the Yogyakarta Principles to protect and promote the rights of sexual minorities, including transgender persons. These are a set of informal principles developed by a distinguished group of human rights experts in a meeting at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in 2006. Despite their informality, they were treated by the court as equivalent to ratified international human rights instruments such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, CEDAW, and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 1984 (specifically, reference was made to their committee reports for interpreting these instruments). Interestingly, in one of its directions to the governments, the Supreme Court states, ‘to create public awareness so that transgenders will feel that they are also part and parcel of the social life and not be treated as untouchables’. Analogizing transgender people to the caste-constructed category of “untouchables” implies that they are considered mutually exclusive from each other and sets apart transgender persons from caste categories, which is not empirically true. These two decisions are pedagogically considered as progressive decisions, as they deployed various tools and techniques to incorporate international human rights laws into domestic decisions. However, they ignored the caste and class underpinnings and the need to use an intersectional lens to understand overlapping identities.[4]

Towards a New Pedagogy

The convergence of the two legal systems and the increasing reference to international law by the domestic courts necessitate a thorough and critical engagement. A new pedagogy demands a deeper involvement with the subject that goes beyond mere theoretical discussions and case laws, inquiring instead into the nature of international law and the role domestic organs have to play in adopting or incorporating it. It is increasingly essential to reaffirm the constitutional channels to channelise or integrate international law into the domestic legal system. The paper proposed a few suggestions, such as firstly, advocating the inclusion of the subject not merely as a distinct theme or head within the Public International Law course, but as a concept that spans across various disciplines, to better understand the influence of international law on such disciplines. Secondly, it is necessary to focus on the formative processes and development of international norms before their implementation into the domestic legal system. While the treaties typically undergo the process of transformation, customary international law is often readily embraced as-is, as the law of the land. A deeper investigation into the nature and character of such norms will provide critical insight and caution when integrating them into the domestic legal system. And, finally, it is essential to adopt an intersectional lens to recognise multiple identities and layers of discrimination that arise from the overlapping identities, rather than prioritising a single dominant identity and compiling numerous international instruments on the topic of this identity merely to internationalise the decisions.

[1] Gramophone Company of India Ltd v Birendra Bahadur Pandey & Ors (1984) AIR 667; M.V Elizabeth v Harwan Investment and Trading Pvt Ltd 1993 AIR SC 1014; Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan (1997) 6 SCC 241; Union of India v Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) 56 ITR 563; M/s Entertainment Network (India) Ltd v M/s Super Cassette Industries Ltd (2008)13 SCC 30; Vellore Citizen Forum v Union of India AIR 1996 SC 2715.

[2] NUS provided a forum where scholars from Asia and throughout the world met to discuss crucial questions, including teaching methods, materials for teaching international law in Asia, the development of skills, and the development of a research culture that fostered scholarship and publication.

[3] The TWAIL scholarship argues that the mainstream international law offers formal and technical norms and structures, holding international law in abstraction from the international society, proceeding with an assumption that the state stands above particular groups, interests, and classes within a nation state.

[4] The recent court decisions that recognised the intersectional discriminations are Patan Jamal Vali v State of Andhra Pradesh (2021) AIR 2190 and M K Ranjitsinh v Union of India (2024) SCC Online SC 570

Paper presented at the ‘Teaching International Law’ Panel, sponsored by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Chair of NLSIU, at the 10th International Conference on International Law: Issues & Challenges, organized by the Indian Society of International Law on 25-27 October, 2024 in New Delhi.

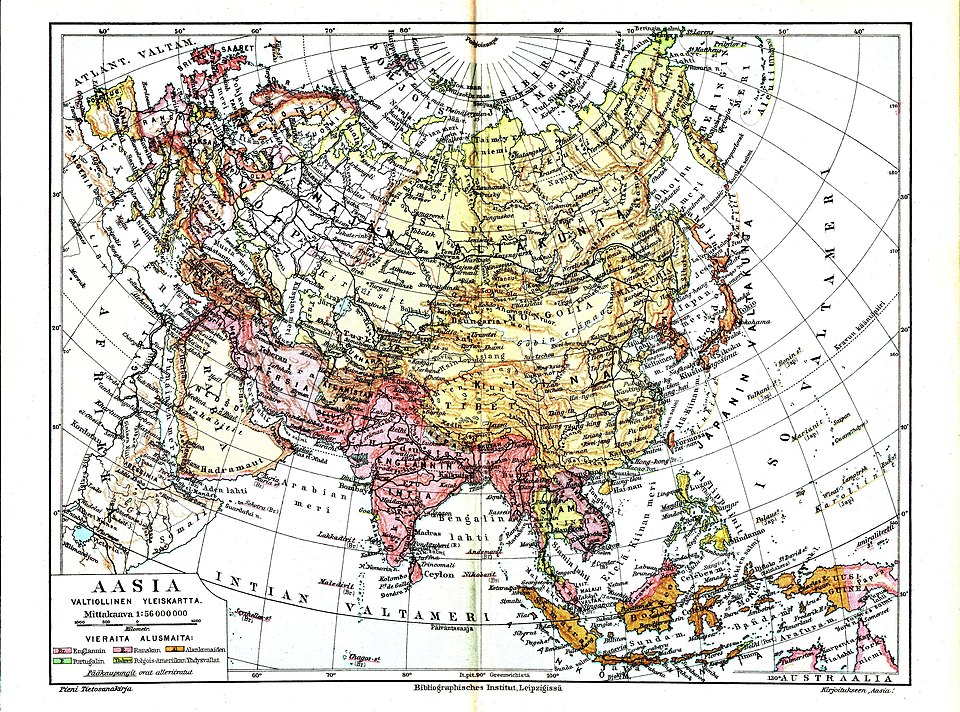

Image credits: From a 1925 encyclopedia, “Pieni Tietosanakirja,” now in the public domain.

Akhila Gangadhar Basalalli

Akhila Gangadhar Basalalli is currently an Assistant Professor of Law and Chair (In Charge), Ministry of Commerce Chair on International Trade Laws, at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru, India. She was also a Visiting Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge. She has obtained her doctoral degree from the Centre for International Legal Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her doctoral thesis examines the implementation of international law in the Indian legal system, identifying the patterns of convergence and integration between them. Her research interests include the interface between international law and domestic law, engagements of judiciary with international law, third world approaches to international law, studies in water law and feminist studies. She has co-edited a book on water laws and authored articles on water resource management and law. She has also published articles on Vachanas and the feminist movement, international rule of law, domestic courts and international law, third-world approaches and feminist approaches to international law.