Teaching International Law: Navigating between Mainstream and Critical International Law

Srinivas Burra

Introduction

This essay is based on my experience of teaching International Law (‘IL’) for over twelve years now. While teaching IL is mainly understood as teaching mainstream IL, it is equally important to understand the importance of teaching critical perspectives on IL. In this essay, I deal with navigating between the mainstream and critical perspectives on IL. The mainstream view of IL tends to emphasise that some fundamental aspects of IL, like the criteria of statehood, the sovereign equality of states and the sources of IL, are well-established and do not require further engagement. The understanding is that these fundamentals are already definite, and no amendments may be made to them. Further, this approach underlines that IL comes into existence through formal sources of law and accordingly its validity is formalised. In response, scholars like Alexandrowicz and R. P. Anand have examined the history of IL and the Law of the Sea and challenged these putative fundamentals of IL. The question I investigate in this essay is whether it is possible to challenge these ‘fundamentals’ in the daily teaching of IL.

Mainstream and Critical Perspectives on IL

At the outset, it becomes necessary to begin with defining mainstream IL. Although an exact definition may be difficult to arrive at, the constituting elements of mainstream IL can be identified- neutrality, autonomy, and independence of rules, i.e., legal formalism and positivism. In contrast, various critical approaches to IL have emerged over the years, such as Critical Legal Studies (‘CLS’), Marxist Approaches to International Law, Third World Approaches to International Law (‘TWAIL’), and Feminist Approaches to International Law. These critical approaches have questioned the fundamentals of IL. For example, CLS centres the ideas of “indeterminacy” of law and that “law is politics”; Marxist critique underlines class as central to understanding IL; TWAIL unravels the colonial foundations of IL and the historical and continuing subjugation of the Global South, and the feminist critique brings the gender question to the field of IL.

These critical perspectives have questioned the autonomy of the legal field, pointed out foundational flaws with legal categories like sovereignty and sovereign equality of states, expanded the understanding of the sources of IL, and laid bare the patriarchal, colonial, and class-based structures embedded into IL. Thus, the fundamentals of IL have been challenged from various perspectives. The challenge for a teacher is to teach these critical perspectives in the classroom without moving away from the mainstream and simultaneously, to make these approaches relevant to students while they look forward to a career in IL.

Methods of Teaching Critical Perspectives on IL

Critical perspectives can be adopted in three ways while teaching the subject. One way is to teach critical IL as a separate course, compulsory or optional. However, this may have a low potential to disturb the fundamentals and such a course will be seen as an “alternative” option to the study of mainstream IL, which only goes to reinforce that an unchanging mainstream framework exists in the first place. The second way is to provide critical reflections on IL towards the end of every IL course. However, this too may present the critical approaches as having limited additional value and the body of work may be understood by students even as something that can be dispensed with, contributing the critical IL’s characterisation as peripheral scholarship. The third way involves teaching IL with critical perspectives embedded in it and not presented as distinct views, so that critical perspectives become a part of everyday teaching.

In certain ways, I have experimented with these three methods and found them helpful in their own ways. However, the third method is more engaging and effective. This involves discussing critical perspectives and counterpoints on every topic in every lecture. For example, while discussing the sovereign equality of states as a vital principle of contemporary IL, it is important to discuss how that principle is defeated with the creation of permanent members in the United Nations Security Council. This method conveys that every topic we discuss, including the fundamental categories of every branch of IL, is not immune to being questioned. Legal pedagogy, in general, is built around the idea that the law and legal institutions are there to elicit “certain” legal solutions. There is a general suspicion that critique leads to uncertainty. The challenge is to debunk this idea. Therefore, the task of critical pedagogy is to present the law not just as a solution to a problem, but as often also a part of the problem (or sometimes the problem itself), and similarly, to present critique of law as not a problem but a part of the solution. The third method approaches this task relatively effectively, by helping to engage critically with every aspect of law. This also has the potential to make teaching and learning participatory and dialogical. To employ the third method however, critical perspectives need to be developed concerning every topic that would be a part of the course syllabus.

Contextualising Critical IL Perspectives

In the use of these teaching methods, the way they are employed is also key to their effectiveness and relevance, and for teaching critical perspectives, contextualising the same amidst immediate circumstances and local histories is crucial. Critical IL methods need to be developed from the histories of IL across the world. For example, in the South Asian context, while dealing with dispute settlement and adjudicatory bodies like the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’), we focus on Judge Weeramantry and his contributions, which are of immense value to critical discourses on IL in South Asia. Along similar lines, we should also note the contributions of others. For example, we rarely discuss the role and the legacy of Judge Muhammad Zafrulla Khan of Pakistan and the controversy around the South West Africa Cases, in which he was asked to recuse himself from adjudication because of his perceived bias towards decolonisation. He was the first Asian president of the ICJ and remains an important figure in its history.

Ethiopia and Liberia submitted two applications in November 1960 before the ICJ against the Union of South Africa relating to the continued existence of the Mandate for South West Africa and the duties and performance of South Africa as Mandatory. The ICJ rejected South Africa’s jurisdictional challenge in 1962. By the time the cases reached the merits stage, Zafrulla Khan was elected to the ICJ for the second time in 1964. The Court delivered its judgment in 1966, dismissing the Applications of Ethiopia and Liberia. The Court held that the Applicants could not be considered to have established any legal right or interest concerning the subject matter. This judgment received large-scale criticism. The Court itself was seen as acting against the interests of the colonial territories and newly independent states. The carefully managed composition of the Court played a crucial role in this judgment. The case was to be decided by a bench of seventeen judges consisting of fifteen permanent judges and two ad hoc judges appointed by the parties. However, three of the seventeen judges did not participate in the judgment. One judge died and another fell ill. The third judge, Zafrulla Khan, was prevented from sitting on the bench in the cases. As a result, fourteen judges decided it. The Court was evenly divided on the judgment. Seven supported the cases and seven opposed them. The president of the Court, Percy Spender from Australia, gave his casting vote for the rejection of applications.

Spender did not want Zafrulla Khan to participate in the cases on the ground that Ethiopia and Liberia approached him to sit as an ad hoc judge during the preliminary stage of the cases. Zafrulla Khan declined this appointment. However, he yielded to Spender’s objection and did not sit on the bench. Zafrulla Khan’s anticolonial views were well known by then, and Spender believed that his presence would tilt the judgment of the Court in favour of the Applicants and against South Africa. Thus, he invoked an unconvincing reason to convince Zafrulla Khan to recuse himself from the cases. These cases were decided when the larger battle for decolonisation was underway.

The same is true regarding Justice Radhabinod Pal, who was an Indian judge at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (‘IMTFE’) or the Tokyo Tribunal. Pal’s dissenting opinion at the Tribunal, declaring its opinion to be victors’ justice built on prevailing narratives of IL, is not only of historical importance but also relevant to understanding how IL operates today. The Tokyo Tribunal was established for the purpose of prosecuting and punishing Japanese perpetrators of crimes at the end of the Second World War. Pal, in his judgment, disagreed with the majority opinion and absolved all the accused. In their doctrinal engagement and conceptual stands, Justice Pal’s perceptive views at the Tokyo Tribunal arguably connect with the later developments in international law. While Pal’s views can be specifically related to the later developments in international criminal law, their relevance to international law in general is of equal significance. The Third World assertion during and after the period of decolonization and the critique of Eurocentrism and hierarchy in international law resonate with Pal’s views in his judgment.

While Pal and Weeramantry, in their opinions, articulated alternative perspectives from within and outside mainstream IL, Khan’s presence on the Bench was perceived with a fear of a defiant outcome. While they were of diverse standpoints, there were similarities in articulating critical positions on mainstream IL, making their inclusion in any teaching of critical IL all the more relevant. Certainly, the historical contexts in which they articulated their opinions are also important.

Moreover, making these voices a part of the curriculum would undoubtedly have a positive reception from students, particularly in a Global South classroom, where it is relatable to the realities they live in. The history of the colonial past, the continuing structural violence in post-colonial realities, economic and technological dependence of the Global South, the political instability and violence resulting from colonial arbitrary division of territories and peoples and the architecture of hierarchy embedded into international institutional mechanisms manifest in different forms in the everyday life of peoples in Global Southern states. Thus, an intimate connection is established between these realities and the Global South classroom because of the material conditions which make that classroom possible. The pedagogical methods and epistemological reimagination framed around the realities of oppression and suffering with the possibilities of emancipation should include the dissenting voices discussed above.

However, while students may respond positively to these unaddressed dimensions, they may continue to find it difficult to relate the aspects to the core of mainstream IL, which presents itself as the substance of the everyday life of IL in dealing with grand legal categories like state, sovereignty, jurisdiction, and war. This perceived dissonance results from engaging with these issues in disconnected ways. Therefore, while we must unearth undocumented and under- documented lived experiences and epistemic challenges in IL, it is critical that we refrain from presenting them as disjointed realities, which prevents us from observing the larger realty within which they are embedded in. This larger reality comprises of historical meta-phenomena including slavery, colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, and imperialism. Though these meta-phenomena are not legal categories in mainstream IL, they structure its past and present. Thus, any critical pedagogy has to make this epistemological connection between the fragmented local histories and larger realities in order to meaningfully relate them to mainstream IL categories.

Conclusion

Teaching critical approaches to IL is significantly dependent on research. There is a paucity of scholarship and therefore textbooks for students that present the various subjects of international law from these perspectives. While it is important to develop textbooks, we need to at least try to develop course-specific reading lists for IL that feature critical approaches as being central to the discussion. The above discussed examples show the presence of alternative perspectives from the Global South practice. There is a need to collate such practices in as many fields of international law as possible. This requires careful exploration and extraction to make them part of the course curriculum and pedagogy.

Paper presented at the ‘Teaching International Law’ Panel, sponsored by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Chair of NLSIU, at the 10th International Conference on International Law: Issues & Challenges, organized by the Indian Society of International Law on 25-27 October, 2024 in New Delhi.

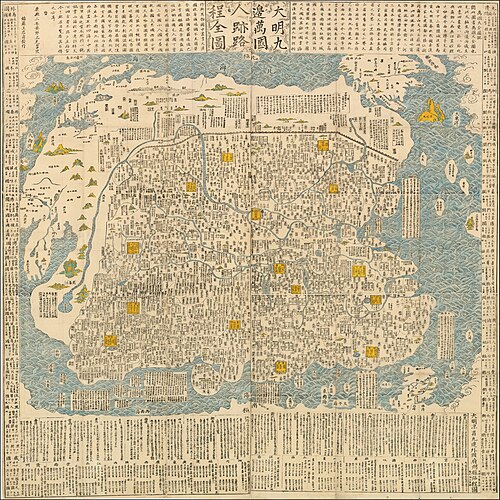

Image credits: By Yahaku Umemura – https://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/54990/complete-map-of-the-nine-border-towns-of-the-great-ming-and-umemura, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91375713

Srinivas Burra

Srinivas Burra is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Legal Studies, South Asian University, New Delhi. Earlier, he worked with the Asian African Legal Consultative Organization (AALCO) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). He is a Vice President of the Indian Society of International law (ISIL) and an Executive Council member of the Asian Society of International law (AsianSIL). His areas of research and teaching include international humanitarian law, international criminal law, law of the sea, refugee law and international legal theories.