Why Is There a Price to Freedom?

Introduction

The primary reason behind arresting someone not yet proven to have committed a crime, is to prevent the ‘triple test’ of risks: (a) the risk of reoffending, (b) flight risk, and (c) the risk of tampering with evidence. Any system of temporarily releasing an accused must therefore effectively address these three concerns. India follows a system of cash bail where liberty is granted to the accused in exchange for money. This is in the form of either a surety or a bond in order to guarantee their appearance in court. If they fail to appear, they forfeit the amount of the bond or face imprisonment.

Cash bail functions on the assumption that the financial risk of losing that money will ensure the accused’s appearance in court and deter them from committing any further crimes. This blog questions the legitimacy of cash bail. I argue that firstly, this assumption of money acting as a deterrent is flawed and cash bail demonstrably falls short of addressing the above-mentioned concerns. Secondly, cash bail disproportionately impacts the working class and thirdly, I use Pierre Bourdieu’s framework of symbolic violence to demonstrate how the courts act as the ruling class to commit symbolic violence upon the working class.

The Purposes of Arrest

In order to argue that cash bail is a form of symbolic violence, I first seek to prove that it does not mitigate against any of the three purposes of arresting a person. First, the premise that cash bail guarantees court appearance by posing a financial risk is questionable. In fact, an accused individual with the financial capacity to post bail presents an arguably higher flight risk since the same resources that enable bail could also facilitate absconding from the jurisdiction. Conversely, those unable to afford bail simply do not have this option. Moreover, the deterrent effect of financial loss may also change with wealth. While forfeiting the bail amount may be devastating for someone with modest means, it may represent a negligible expense for the affluent. The effectiveness of the system therefore changes with a person’s wealth.

Secondly, poverty alone cannot be used as a reliable predictor of criminal behaviour. Cash bail’s approach to public safety is problematic since it relies on the ability to pay a certain amount as a guarantee against not committing future crimes. Public safety should ideally be a universal concern, entirely independent of an accused individual’s wealth. The current system, where money is used as a means for release, creates an inequitable situation where those with resources are more likely to be free while those without, who may not possess a greater threat, remain incarcerated.

Thirdly, cash bail also does not reliably mitigate against evidence tampering. The inherent potential for corruption within the criminal justice system allows for the misuse of financial means. An accused with the ability to post bail may also possess the same resources that could be used to tamper with evidence or obstruct investigations. In stark contrast, indigent defendants, lacking such means, often remain incarcerated solely due to their inability to post bail. This is not to suggest that affluent individuals are more likely to exploit the system; rather, it shows that wealth by itself cannot be a differentiating factor in fulfilling these three criteria.

The Disproportionate Effect

Since cash bail does not address the reasons of arrest, it is important to look at the set(s) of people most affected by this system. NCRB’s Prison Statistics 2022 reveal that India has more than 4,00,000 undertrial prisoners, which means that there are three undertrials for every four prisoners in India’s prison system. 85% of the undertrials in prisons are people from the minority communities, and 65% of them are either illiterate or only literate to the 10th grade. This is despite the fact that marginalised communities constitute 79% of the total population. The figures reveal a distinct demographic profile of those affected by the cash bail system, with marginalised communities being overrepresented in the undertrial population. The overrepresentation of marginalised groups in the undertrial population, alongside a conviction rate of only 60% shows that there are systemic flaws that affect how the socio-economically disadvantaged are processed in our criminal justice system.

38.21% of all prisoners have an annual family income less than 30,000 and perhaps even more alarmingly only 1.4% of the prison population belong to the highest income bracket. This significantly hampers their ability to earn a decent livelihood and meet their daily requirements, especially when in such situations, the state demands a cash sum from undertrials as a precondition to their release for a crime they are not yet proven to have committed.

This shows that cash bail cannot successfully mitigate against the three purposes of arrest, and it disproportionately impacts the marginalised class. In the next section, I explain what Pierre Bourdieu describes as ‘symbolic violence’ and why the Court should be considered a part of the ruling class.

Bourdieu’s Framework

Given the failure of cash bail to achieve its stated purposes and its disproportionate impact on the poor, it becomes crucial to examine why this system persists despite its obvious flaws. In this section I first explain Pierre Bourdieu’s framework of symbolic violence and then use that framework to argue that due to its distinct demographic profile, the Court wields enormous cultural and economic capital, and should be categorised as a part of the ruling class.

A. Symbolic violence

Bourdieu argues that social hierarchies, inequality, and their effects stem from ‘symbolic violence’ and not from physical violence or coercion. This form of violence works by shaping individual behaviour and perceptions through the manipulation of ideas and beliefs.

Bourdieu extends Marx’s concept of economic capital. Marx argues that economic capital is the basis of the ruling class’s authority to include nonmaterial forms of capital, such as cultural, social, and symbolic capital. Bourdieu complements Marx by adding a theory of symbolic domination to help us understand material exploitation. In this context, money, though an economic factor, transforms into a tool for symbolic domination.

He then defines the ruling class as not only those controlling economic capital such as industrialists, large landowners, corporate executives but also controllers of cultural capital, such as educational and professional elites. Institutionalised cultural capital is particularly potent because it combines the prestige of innate property with the merits of acquisition, masquerading as natural ability while concealing the class privileges that facilitated its development. Educational qualifications are a perfect example: while they appear to be merit-based, they actually reflect underlying socioeconomic advantages that enabled their attainment in the first place.

To understand how symbolic violence operates through the cash bail system, it is essential to identify who constitutes India’s ruling class and how the judiciary functions within this framework. The judiciary, while constitutionally independent, operates as part of this class structure through institutional mechanisms that perpetuate existing hierarchies.

The ruling class uses symbolic violence as a method of stopping the working class from questioning these social hierarchies and inequalities within various institutions. They achieve this by monopolising access to various forms of capital and suppressing challenges to the system’s legitimacy. Bourdieu refers to this as “complicitous silence,” a condition in which institutions with the power and ability to create change, despite recognising the severity and impact of these inequalities, remain unresponsive. Regardless of intent, the cash bail system creates a disparity that disadvantages economically weaker sections. In the next section, I argue that given the demographic composition of the Court and its monopoly in the legal field, it should be considered a part of the ruling class.

B. The Ruling Class and the Legal Field

33% of Supreme Court judges and 50% of High Court judges are relatives of existing judges; further, the Supreme Court is still largely composed of upper caste men. Most judges of the Supreme Court come from wealthy and upper-middle-class backgrounds, possessing both economic capital and the ability to shape cultural capital through their judgements and societal status. Therefore, when sitting in positions of power and wielding economic and cultural capital, the judiciary, through its judges, acts as the ruling class. The inherent biases that come with one’s socio-economic experience cannot be ignored. When most judges have a distinct socio-economic experience from that of most persons facing the brunt of the cash bail system, their refusal to challenge the legitimacy of the system is questionable.

These patterns, replicating the class hierarchy through economic and opportunity barriers, create what Bourdieu terms ‘habitus.’ Habitus is the disposition shared within a class, through which they act to naturalise inequality as a legitimate procedure. The judiciary, largely comprised of the members of the ruling class, replicates the inequalities through their decisions. Since the ruling class controls material resources, education, and perhaps most importantly, information, society often stops questioning the fairness of such systems. These systems operate as instruments of domination by making arbitrary and hierarchical power relations appear natural and inevitable. It is within this theoretical framework that the Indian judiciary’s response to cash bail must be examined, particularly how institutional authority perpetuates these dynamics through complicitous silence.

The legal field is the site of competition for monopoly of the right to determine the law, where those with the necessary forms of capital maintain advantageous positions. The legal field has internalised an inherently unfair system to the point where it goes unquestioned. The legal field, whether intentionally or not, perpetuates the interests of dominant groups, with cash bail acting as a vehicle for symbolic violence. In this scenario, therefore the court and government being comprised largely of the dominant groups controlling economic and social capital, represent the ruling class. The next section shows how the ruling class uses “cash bail” to exert symbolic violence upon the working class.

The Court

Despite acknowledging the problems with cash bail, the Court has failed to challenge its existence, instead engaging in what Bourdieu terms complicitous silence. Through an analysis of the Supreme Court’s bail jurisprudence, this section establishes that the Court acts in tandem with the ideas of the ruling class, perpetrating symbolic violence on the poor.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognised the dire conditions in Indian prisons and acknowledged that most inmates are undertrials from disadvantaged backgrounds. While the Court has ordered the release of many prisoners (Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar), issued guidelines (Hussain v. Union of India), and even suggested enacting a specific bail statute (Satendra Kumar Antil v. CBI), it has consistently stopped short of questioning the existence of the cash bail system.

The 2022 judgment in Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI exemplifies the judiciary’s complicitous silence. The judgement established categories for standardised bail conditions but entirely failed to question why a person’s wealth should determine pre-trial liberty in the first place. The Court consistently holds that the object of bail can neither be punitive nor preventative and that the deprivation of liberty must be considered a punishment, unless it is required to ensure that an accused person will stand his trial when called upon. However, despite this the Court has consistently declined to declare the cash bail system itself unfair, instead limiting interventions to specific categories of undertrials. Courts have failed to develop ‘individualised and specialised processes’ and instead continue importing factors from the trial process that remain unjustified outside of the punitive detention process. The measures the Court has taken thus far do not solve the issue of the existence of an unfair system; they mitigate the problems it creates. Despite a call for cash bail reforms, these reforms remain incomplete because they fail to address the fundamental assumption that financial risk is necessary to ensure that the accused appear in Court. The Court, therefore, does not remedy the larger issue of the system’s legitimacy but, rather, curbs the negative consequences of the system on a case-by-case basis. This approach precisely aligns with Bourdieu’s concept of complicitous silence, where institutional authority is exercised not through explicit coercion but through failure to address the pertinent issue.

The Court in Moti Ram v. State of MP recognized that the poor are priced out of their liberty in the justice market, with Justice Krishna Iyer criticizing the magistrate’s insistence on excessive bail and sureties from an indigent person. It acknowledged that economic and social disabilities enable the rich to obtain freedom while the poor languish in jail yet, its intervention was limited to reducing bail amounts, rather than questioning the validity of cash bail itself. The Court has continued to operate within the narrow sphere of modifying bail amounts or releasing prisoners.

More recently, in Hussain v. Union of India, the Court acknowledged that undertrials are languishing in jail for long periods, despite being granted bail, due to their inability to furnish bail Yet, the Court chose to limit its response to directing expeditious trials rather than addressing the root cause, the cash bail system itself. India’s prisons are overcrowded, and practices such as torture and manual scavenging by prisoners are still prevalent in multiple states despite an explicit ban; further, the non-provision of essentials such as sanitary napkins at a majority of prisons leads one to question whether the system has become a means of pre-trial punishment.

Therefore, the Court must be reminded that any time spent in jail because of a lack of wealth is injustice; the undertrial is still an accused and must be treated fairly and not subject to the dire conditions in prisons for no fault of her own. This reluctance to act, even when acknowledging fault lines, is what Bourdieu calls the abuse of institutional authority. The most successful ideological effects, as he notes, are those that ask no more than complicitous silence, a sentiment that perfectly exemplifies the current state of affairs.

The cash bail system is ineffective because it does not reliably guarantee Court appearances, as those with means might still pose flight risks, nor does it necessarily ensure public safety. The Court continues to uphold cash bail even when there is clear evidence of its inequitable outcomes. Despite the Court’s apparent awareness of systemic inequalities, it has consistently refused to question the premise that liberty should be contingent upon financial capacity.

The cash bail system is used by the Court as a tool in the hands of the ruling class to perpetuate and replicate existing inequalities. The poor continue to be kept in prisons despite holding no more flight risk or threat to public safety than a rich person accused of the same crime. This takes away the fair chance to make a livelihood and uplift themselves from poverty. Through this system, the poor continue to remain poor while the rich are free to continue with their businesses and jobs despite being accused of the same crime.

Alternatives

There are provisions in the law that try to solve the problems of cash bail. However, when closely examined these provisions fail to mitigate against issues of cash bail. Section 479 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNSS) acknowledges prison overcrowding and allows for bail without cash requirements, however it paradoxically denies bail in cases involving multiple charges. Therefore, when most persons who are facing incarceration are not even eligible for release under the section, the mechanisms that the law creates to mitigate against the problems of cash bail clearly fail.

Furthermore, the statute exhibits inconsistency in its approach to undertrial release. While it permits the release of women, children, and the sick, this is excluded in instances where they are reasonably believed to have committed crimes with a penalty of death or imprisonment for life. Such provisions effectively eviscerate the presumption of innocence, failing to distinguish between an accusation of a heinous crime and a conviction.

In 2023, the government introduced a scheme offering financial assistance of up to ₹40,000 to help individuals secure cash bail. However, this measure also fails to address the underlying structural issues of the bail system; rather than challenging the inequalities, it reinforces the status quo and offers only limited relief. By providing government money to secure bail, the state eliminates any personal financial risk for the accused, completely undermining the foundational assumption that cash bail works because individuals fear losing their own money.

Therefore, when statutory provisions are largely unable to mitigate the adverse effects of cash bail, and the government is not willing to challenge the system, it becomes imperative that the judiciary steps in to address this issue. The reluctance of the Court to question the legitimacy of the cash bail system is what reinforces the class inequalities and works as a form of symbolic violence upon the working class. The question then is: what could be the solution to this problem?

The United States, which had a similar system of cash bail, phased out similar provisions through Eighth Amendment jurisprudence and subsequent state legislation, eliminating cash bail in many areas. Some states have not entirely abandoned the system but have introduced risk assessment algorithms, assigning points for various factors to help judges remain unbiased and consider the accused’s socioeconomic circumstances in bail determinations. India could certainly adopt such a system, albeit with significant modifications to fit our unique social context.

Some might suggest plea bargaining as an alternative, but this too, presents its own challenges. It often fails to account for the relative power dynamics between parties, and individuals are frequently reluctant to enter guilty pleas, as it typically involves compulsory incarceration, as opposed to taking a chance on acquittal. While the BNSS attempted to introduce community service, its application is limited to only six offenses, and its real-world implementation remains largely unclear. The failure of the statutory provisions and the complicitous silence of the Court highlight the urgent need to initiate a broader discourse on reforming the current system and developing more equitable alternatives.

Conclusion

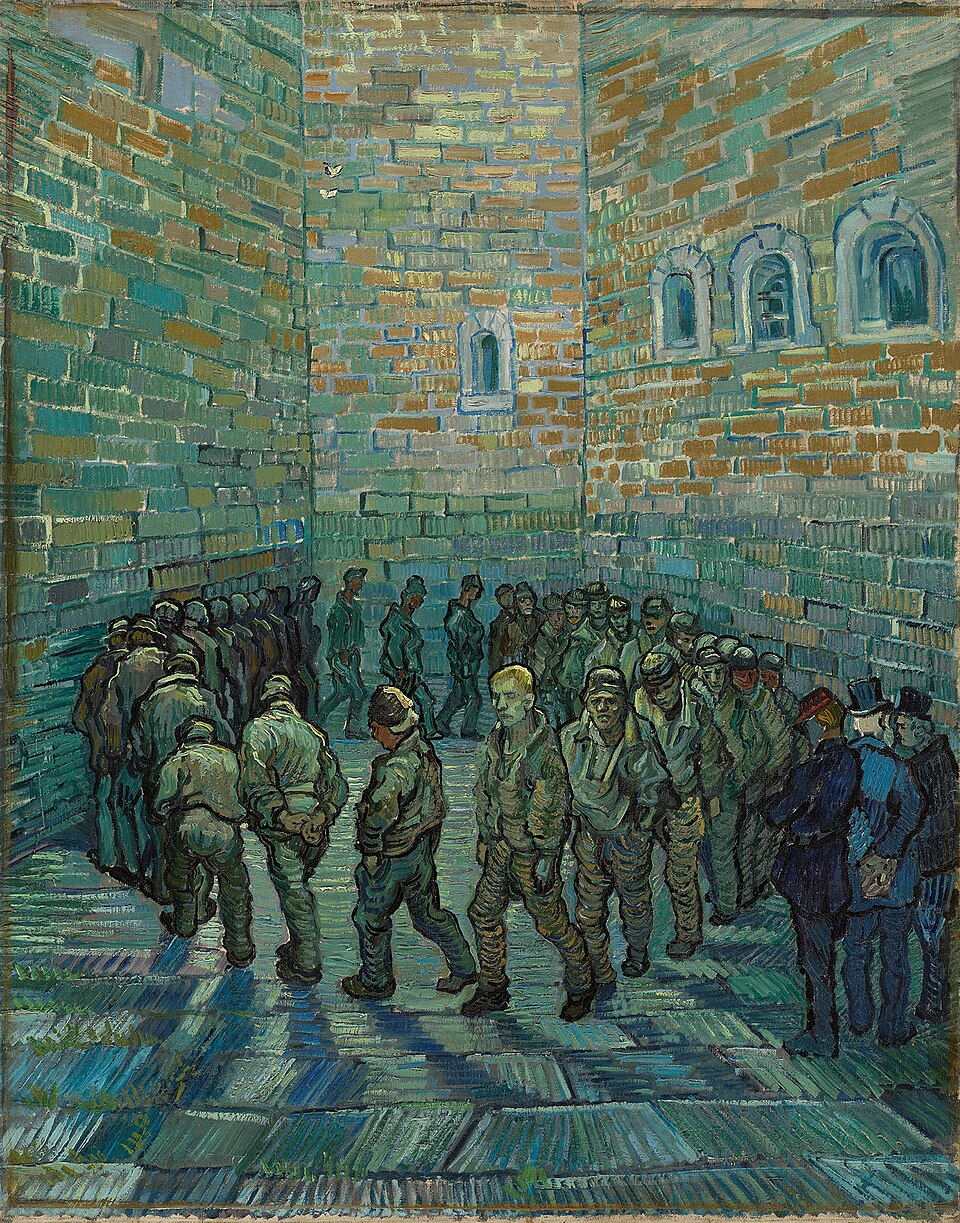

Indian prisons serve as a stark reflection of the societal stratification that persists, illustrating the symbolic violence perpetuated by the ruling class. India’s bail jurisprudence operates on the flawed assumption that money effectively mitigates the purposes of arrest. The statutory provisions themselves disproportionately affect the economically weaker, creating a formidable barrier to even expecting equitable outcomes from the judicial system. Even if ultimately acquitted, a poor defendant endures significantly more hardship than a wealthy defendant who is found guilty. It is only after a verdict is pronounced that both accused individuals are placed on a partially equitable playing field.

This critique is not meant to suggest institutional apathy; in fact, Courts have shown awareness of the systemic issues and prison overcrowding. However, the central question still haunts us: why is there a price to freedom? While there is no definitive answer, when Courts establish thresholds that disproportionately impact poor undertrials, they engage in a form of symbolic violence. It is long overdue to rethink how we grant bail. This blog sought to question the legitimacy of the cash bail system, arguing that its persistence constitutes a form of symbolic violence. In remaining silent despite the system’s evident injustices, the judiciary becomes complicit in reinforcing class hierarchies through symbolic violence.

Tanishq Desai

Tanishq is a second-year law student at National Law University, Delhi with a keen interest in criminal and constitutional law.The author can be reached at tanishq.desai24@nludelhi.ac.in